The most foundational aspect of Chinese medical thought is that of Qi (pronounced chee). In its most basic sense, Qi is energy, or vital energy. It is energy that flows in our bodies, around our bodies, in the air and earth around us, in the plants, and is connected to other unseen forces in nature, such as electricity. (It’s interesting to note that the Chinese word for electricity is DianQi, 电氣, or electric Qi.) Nathan Sivin continues: “At the same time [Qi] is matter, whether condensed or dispersed, perceptible or imperceptible, breath or blood; the vital energy within matter that keeps it organized and makes growth possible; and the force in living matter that influences other things. These ideas are not separated in early medical Chinese thought. One word was enough” (1). One word describes such a powerful and universal force and carries with it so much meaning and depth.

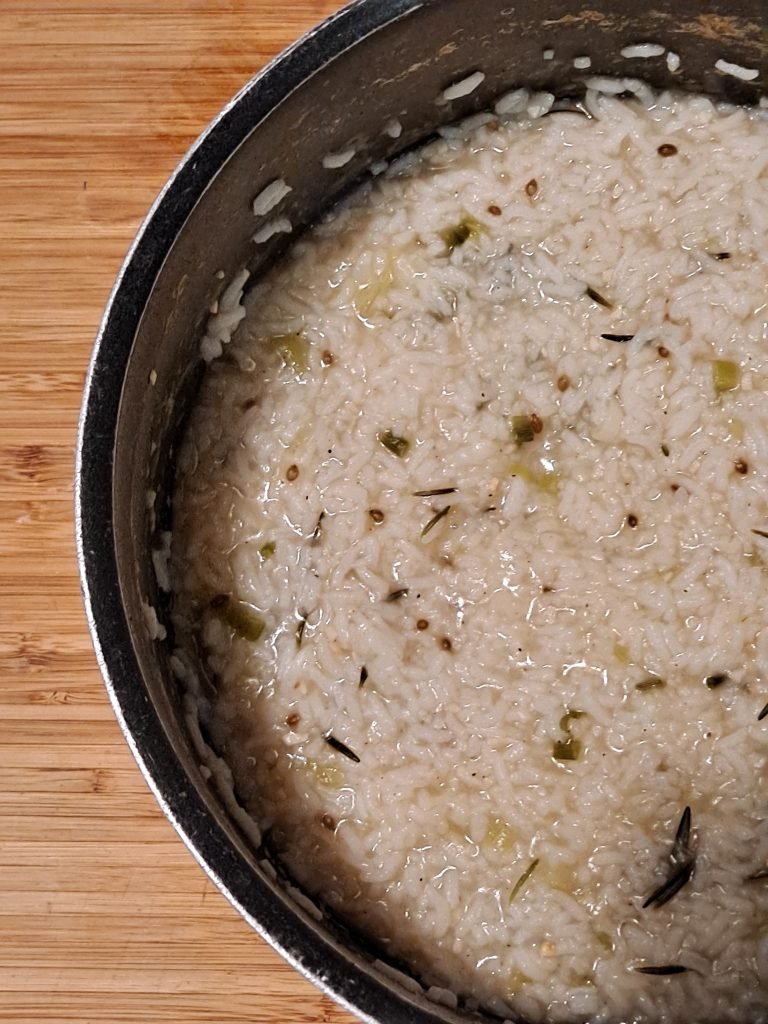

Part of that depth can be seen in its Chinese character. The character for Qi (氣) contains two major parts: that on the top and right side, and that underneath. On the top are 3 lines flowing together, indicating a stream of air or breath. One of the definitions for Qi is that of breath. The three lines can be viewed as connecting to Dao De Jing 42 which states that “One becomes two, two becomes three, and three becomes the ten thousand things.” One, the Dao, becomes two, yin and yang, which becomes three, such as in the character for Qi, and then ten thousand things, relating to Qi’s ability to be in all things. Underneath is a popping rice grain. Rice is a dietary staple in much of the world, and the Chinese people are the number one consumers of it (2). Their vital food source is in the character for vital energy.

At least two explanations of this character are as follows:

- This character can be a pictogram of steam coming off cooked rice. While the Qi is also in the rice itself, this character is showing that Qi is the more ethereal aspect of the cooked rice. Qi is in the steam.

- In my Foundations to Chinese Medicine class, my teacher gave us a complex diagram showing the relationship between certain types of Qi and the organs of the body and how Qi flows throughout the body. One thing that was drilled into us was that two of the major sources of Qi in the body are food and air. According to the ancients, food enters the body, goes into the Stomach to be physically processed, and then to the Spleen to be energetically processed. The Spleen then sends those nutrients up to the Lung, which has been breathing in Qi-filled air. The Lung then disseminates those nutrients to the rest of the body. This ability of the Lung can be thought about like oxygen exchange through the capillaries and alveoli of the Lung lobules. That oxygen travels through the blood to nourish the body. With this perspective, the character for Qi is a description of two of the major sources of Qi in the body – food and air.

Qi flows through pathways throughout the body. The Yellow Emperor’s Inner Canon: Spiritual Pivot chapter 12 relates these pathways to rivers. Just as rivers flow through the land, branching off, connecting different places, and connecting to each other, the same is with the rivers in the body. These rivers of Qi in the body are also called meridians or channels. As the Yellow Emperor says it:

“When viewing the twelve channels of a man from outside, they are like the twelve waters, when viewing them from inside, they link the five solid organs and the six hollow organs.”

Yellow Emperor’s Inner Cannon: Spiritual Pivot (3)

For more on the qualities and attributes of Qi, keep reading future articles!

Sources:

- Fruehauf H. Classical Chinese Medicine: An Introduction to the Foundational Concepts and Political Circumstance of an Ancient Science. Portland, OR: Hai Shan Press; 2019: 13.

- Top 10 Most Rice-Consuming Countries Worldwide 2023. DigiBiz. Published May 10, 2023. Accessed July 2023. https://digibizworld.com/top-most-rice-consuming-countries/

- Wang Bing. Translated by Wu L, Wu Q.Yellow Emperor’s Canon of Internal Medicine: Chinese-English Edition. China Science & Technology Press: 2010.